Class 14: Game Theory II

02-26-2020

“Can we do better?”

Let \(s\) be the current state in a game and \(s_1, s_2, \dots, s_n\) the new states where we can go. Then we already know that:

\[g(s) = mex(g(s_1), g(s_2), \dots, s(s_n))\]

But, if each \(s_i\) can be seen as an independent game, then applying the Sprague-Grundy theorem we can compute:

\[g(s_i) = g(a_1) \oplus g(a_2) \oplus \dots \oplus g(a_m)\]

Where \(a_i\) depends of \(s_i\).

This kind of games where a move divides the game into subgames that are independent of each other are commonly found. Let’s call them Grundy’s games. Here are some examples:

First problem

Problem taken from Competitive Programmer’s Handbook, chapter 25. Page 240.

Problem: The problem is the same as the game of Nim but now, in each turn a player can choose a pile and divide it into two non-empty piles such that the new two piles are of different size.

We can solve the problem using WL-states or Grundy numbers, but the numbers of states are too much (can you compute it?). Nevertheless, we can notice that if we take pile \(s_i\) and divide it into piles of size \(a_1 \land a_2 \mid a_1 + a_2 = s_i\), then we can see \(a_1 \land a_2\) as independent subgames. So, we have:

\[g(s_i) = mex(\{a_1 \oplus a_2\} \mid a_1 \not = a_2 \land a_1 + a_2 = s_i)\]

Can you implement it?

Second problem

Problem taken from E-maxx Sprague-Grundy theorem. Nim.

Problem: You have \(n\) rectangles in a row. There are two players, in each turn a player chooses a rectangle and writes a cross on it. It is forbidden to put two crosses next to each other (in adjacent cells). As usual, the player without a valid move loses. If both players play optimally. Who will be the winner ?

Example of an instance of the game when \(n = 6\)

When a player writes a cross in a cell \(i \mid 2 \leq i \leq n - 1\) we are bassically dividing the game into two independent subgames of size \(i - 2\) and \(n - i - 1\) because the adjacent cell of the \(i\)-th rectangle are virtually destroyed. Then, taking care of the corner cases (when a player writes a cross in the first or last rectangle), we can deduce that \(g(n)\) can be expressed in this way:

\[g(n) = mex(\{g(n - 1)\} \cup \\ \{g(i - 2) \oplus g(n - i - 1) \mid 2 \leq i \leq n - 1 \})\]

Then we can implement this idea in \(O(n^2 \log n)\) or in \(O(n^2)\). Can you implement it?

So far we have learned how the characteristic property allow us to solve problems using WL states. Then we learned how Grundy numbers can solve all the problems that are solvable using WL states. After that we notice how the Sprague-Grundy theorem solves a much rich variety of problems. Now, one question left is if all the impartial combinatorics games can be solved using the Sprague-Grundy theorem. Sadly, it is not always the best approach, yet we can always start using the characteristic property and seek for improvements. For example, let’s try this problem:

Problem taken from Game theory - Thomas S. Ferguson. Chapter 1. Page 13.

Problem (Staircase Nim): A staircase of \(n\) steps contains chips on some of the steps. Let \((x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)\) denote the position with \(x_i\) chips on step \(i \mid 1 \leq i \leq n\). A move in this game consists of moving any positive number of chips from any step \(i\) to the next lower step \(i - 1\). Chips reaching the ground (step 0) are removed from play. The game ends when all chips are on the ground. Both players play optimally and alternating turns. If the last to move wins, who will be the winner ?

We can solve the problem using Grundy numbers or WL states, but the complexity would be at least \(O(x_1 \cdot x_2 \cdot \dots x_n) = O(x^n)\) where \(x = \max(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)\). We need something better.

With some trial and error we can notice that if we define our state as the chips that are only in odd steps, then all the moves of chips from even positions are meaningless because let \(i\) be and even number, then if a player moves \(z\) chips from step \(i\) to step \(i - 1\), then in the next turn the other player can move \(z\) chips from step \(i - 1\) to step \(i - 2\), so the number of chips in the odd steps have not changed. Therefore, we only care about the chips in odd positions. Evenmore, in the same fashion of Bouton’s theorem, we can prove that:

\[(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_{n}) \in \mathbb{L} \leftrightarrow \displaystyle\bigoplus_{\substack{i = 1\\ i += 2}}^{n}x_i = 0\]

The proof of this affirmation is very similar to the proof of Bouton’s theorem, but if you need some help you can read this answer.

Now, we can solve our problem in \(O(n)\).

Understanding that the definition of our state can affect the complexity of our solution is very important. Moreover, it is good to know in advance games like the Staircase Nim in order to solve some hard problems (that may require more advances techniques) like these:

So far in all the problem we have solved the winner was the one who makes the last move, but what happened when the loser is the one who makes the last move ? Well, in this kind of games we can not use the Sprague-Grundy theorem, but we can use the other approaches to solve them and it may usually requiere an extra analysis. This kind of problems are know as misère games, here is an example:

Problem (Misère Nim): The problem is the same as the game of Nim, but now it has the misère condition.

First, try to solve this problem by yourself. Try the get the optimal strategy. If you give up you can find the solution in Game theory - Thomas S. Ferguson. Chapter 1. Page 11.

We have already studied some techniques for solving impartial combinatorics games, but you may be wondering how to solve partizan games. The fact is that we may use WL states or Grundy numbers to solven them, yet a general backtracking solution using the characteristic property is better in this kind of games because there can be a draw. Then, we need to differenciate a draw, a winning state and a losing state. One way to achieve this is to define an utility function that assigns a value to each state. For example:

\[ \text{utility}(state) =, \begin{cases} 1 & \quad \text{If state is a winning state}\\ 0 & \quad \text{If state is a draw}\\ -1 & \quad \text{If state is a losing state}\\ \end{cases} \]

In a partizan two-player game, as each player may play optimally, there would be a player that will try to obtain the maximum utility, whereas the other player will try to obtain the minimum utility. In other words, when both players play optimally, basically the first player will try all the moves and will choose the move that gives him the maximum utility, then the second player will choose the move that gives the first player the minimum possible utility, and so on.

Then, we can implement something like this:

namespace Minimax {

int utility (State);

int minVal (State);

int maxVal (State);

}

namespace Minimax {

int utility (State s) {

return the weight of the state s

}

int minVal (State s) {

if (s is a terminal state) {

return utility(s);

}

// First, assume the worst scenario

int ret = max_utility_value;

for (State s' reachable from s) {

ret = min(ret, maxVal(s'));

}

return ret;

}

int maxVal (State s) {

if (s is a terminal state) {

return utility(s);

}

// First, assume the worst scenario

int ret = min_utility_value;

for (State s' reachable from s) {

ret = max(ret, minVal(s'));

}

return ret;

}

}

This idea (basically a simulation of all possible scenarios) is achieved when the first player calls Minimax::maxVal(initial_state). As minVal calls maxVal and maxVal calls minVal, we need to declare the interface of these functions and we are grouping them in a namespace to keep them in order. Now, using this framework we can solve a variety of problems like chess, go, checkers, etc. The only problem is that this solution is exponential, yet it is important to understand it because this idea is the base for other solutions.

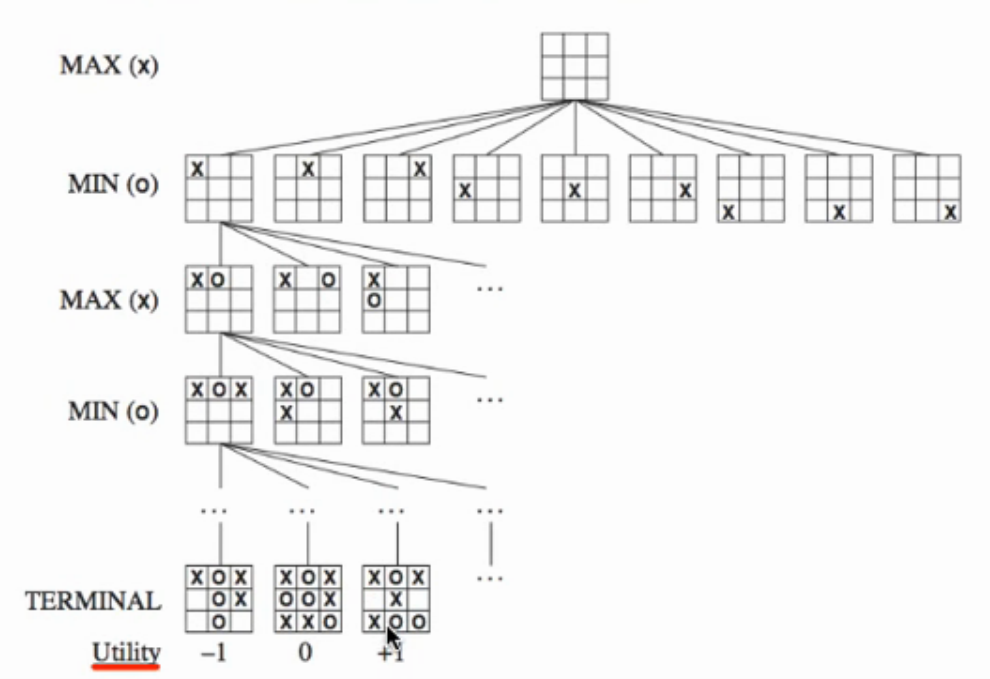

As an example we can solve the Tic Tac Toe game using this framework. When doing it the recursion tree may looks something like this:

The image was taken from this video

Moreover, you may notice that this framework is simply a backtracking, but for its importance (and maybe for the Rumpelstiltskin Principle) it is called the Minimax algorithm.

You may also be interested in watching Coding Challenge 154: Tic Tac Toe AI with Minimax Algorithm for a visual implementation of the Minimax algorithm for Tic Tac Toe.

Now, we known how to solve partizan combinatorial games in exponential time, but there is an simple, yet powerful optimization we can do. What happen if I am executing maxVal function and I already found the maximum possible utility ? What happen if I am executing minVal function and I already found the minimum possible utility ?

Well, in these scenarios there is no need to keep searching, we already know the final utility of our current state, then we can prune the search. This simple optimization will improve our solution a little, yet it may usually be enough for problems in competitive programming. For example, let’s practice this optimization solving The game of 31.

Try it by yourself for a while. You may end up with something like this:

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

const int LEN = 100, N_CARDS = 6;

int ct[N_CARDS + 1];

char moves[LEN];

bool ans;

namespace Minimax {

int minVal ();

int maxVal ();

void solve ();

}

namespace Minimax {

int sum;

const int WIN = 1;

const int FAIL = -1;

int minVal () {

if (sum > 31) return FAIL;

int ret = WIN;

for (int card = 1; card <= N_CARDS and ret != FAIL; card++) {

if (ct[card]) {

ct[card]--, sum += card;

ret = min(ret, maxVal());

ct[card]++, sum -= card;

}

}

return ret;

}

int maxVal () {

if (sum > 31) return WIN;

int ret = FAIL;

for (int card = 1; card <= N_CARDS and ret != WIN; card++) {

if (ct[card]) {

ct[card]--, sum += card;

ret = max(ret, minVal());

ct[card]++, sum -= card;

}

}

return ret;

}

void solve () {

sum = 0;

int id;

for (id = 0; moves[id]; id++) {

ct[moves[id] - '0']--;

sum += moves[id] - '0';

}

int res = (id & 1) ? minVal() : maxVal();

ans = res == WIN;

}

}

inline void print () {

printf("%s %c\n", moves, "BA"[ans]);

}

inline bool read () {

if (cin.getline(moves, LEN)) return true;

return false;

}

inline void clear () {

fill(ct, ct + N_CARDS, 4);

}

int main () {

while (read()) {

clear();

Minimax::solve();

print();

}

return (0);

}This optimization is what is known as Alpha-Beta prunning. In fact, the Minimax and Alpha-Beta prunning have even more interesting things, yet this is out of the scope of this training.

You may also be interested in watching this documental of AlphaGo. Here is the trailer.

Recommended readings:

- Game theory - Thomas S. Ferguson. Chapter 1-4

- Competitive Programmer’s Handbook, chapter 25

- E-maxx Sprague-Grundy theorem. Nim

- Search: Games, Minimax, and Alpha-Beta

You can find the contest here.

A: Misère Nim

Misère Nim

Check the section Misère Games of this class.

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#define all(A) begin(A), end(A)

#define rall(A) rbegin(A), rend(A)

#define sz(A) int(A.size())

#define pb push_back

#define mp make_pair

using namespace std;

typedef long long ll;

typedef pair <int, int> pii;

typedef pair <ll, ll> pll;

typedef vector <int> vi;

typedef vector <ll> vll;

typedef vector <pii> vpii;

typedef vector <pll> vpll;

int main () {

ios::sync_with_stdio(false); cin.tie(0);

int tc;

cin >> tc;

while (tc--) {

int n;

cin >> n;

bool all_one = true;

int nim_sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

int x;

cin >> x;

all_one &= (x == 1);

nim_sum ^= x;

}

if (all_one) {

if (n % 2 == 0) cout << "First\n";

else cout << "Second\n";

} else {

if (nim_sum == 0) cout << "Second\n";

else cout << "First\n";

}

}

return (0);

}B: Euclid’s Game

Euclid’s Game

Simulate the game using Minimax.

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#define WIN 1

#define FAIL -1

using namespace std;

typedef long long ll;

ll num_1, num_2;

int minVal(ll, ll);

int maxVal(ll, ll);

int minVal(ll _max, ll _min) {

if (_max % _min == 0) return FAIL;

int res = WIN;

for (ll k = (_max / _min) * _min; res != FAIL and k >= 1; k -= _min)

res = min(res, (_max == k) ? FAIL : maxVal(max(_max - k, _min), min(_max - k, _min)));

return res;

}

int maxVal(ll _max, ll _min) {

if (_max % _min == 0) return WIN;

int res = FAIL;

for (ll k = (_max / _min) * _min; res != WIN and k >= 1; k -= _min)

res = max(res, (_max == k) ? WIN : minVal(max(_max - k, _min), min(_max - k, _min)));

return res;

}

int minimax(ll a, ll b) {

return maxVal(a, b);

}

int main() {

while (scanf("%lld %lld", &num_1, &num_2), num_1 and num_2)

puts(minimax(max(num_1, num_2), min(num_1, num_2)) == WIN ? "Stan wins" : "Ollie wins");

return (0);

}C: Box Game

Box Game

You can use Minimax to get a pattern.

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

namespace Pattern {

int minVal(int, int);

int maxVal(int, int);

int minimax(int);

void getAnswers(int);

}

namespace Pattern {

const int WIN = 1;

const int FAIL = -1;

int minVal(int _max, int _min) {

if (_max == 1 and _min == 1) return WIN;

int ret = WIN;

for (int it = 1; 2 * it <= _max and ret != FAIL; it++)

ret = min(ret, maxVal(max(it, _max - it), min(it, _max - it)));

return ret;

}

int maxVal(int _max, int _min) {

if (_max == 1 and _min == 1) return FAIL;

int ret = FAIL;

for (int it = 1; 2 * it <= _max and ret != WIN; it++)

ret = max(ret, minVal(max(it, _max - it), min(it, _max - it)));

return ret;

}

int minimax(int k) {

return maxVal(k, 1) == WIN;

}

void getAnswers(int limit) {

for (int k = 2; k <= limit; k++)

printf("%3d : %s\n", k, minimax(k) ? "Alice" : "Bob");

}

}

const int Alice = 0;

const int Bob = 1;

int n;

map <int, int> winner;

void fillBobPositions() {

for (long long k = 3; k <= 1e9; k = k * 2 + 1) winner[k] = Bob;

}

int main() {

//Pattern::getAnswers(35);

fillBobPositions();

while (scanf("%d", &n), n) puts(winner[n] == Alice ? "Alice" : "Bob");

return (0);

}D: Stones

Stones

Simulate the game using Minimax.

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#define WIN 1

#define FAIL -1

#define UNVISITED -2

using namespace std;

const int MAX_N = 1010;

int8_t memo[MAX_N][MAX_N][2];

int minVal(int, int);

int maxVal(int, int);

int minVal(int limit, int n) {

if (n == 0) return WIN;

if (memo[limit][n][0] != UNVISITED) return memo[limit][n][0];

int ret = WIN;

for (int k = 1; k <= limit and ret != FAIL; k++)

ret = min(ret, maxVal(min(2 * k, n - k), n - k));

return memo[limit][n][0] = ret;

}

int maxVal(int limit, int n) {

if (n == 0) return FAIL;

if (memo[limit][n][1] != UNVISITED) return memo[limit][n][1];

int ret = FAIL;

for (int k = 1; k <= limit and ret != WIN; k++)

ret = max(ret, minVal(min(2 * k, n - k), n - k));

return memo[limit][n][1] = ret;

}

bool minimax(int n) {

return maxVal(n - 1, n) == WIN;

}

int main() {

int n;

memset(memo, UNVISITED, sizeof memo);

while (scanf("%d", &n), n) puts(minimax(n) ? "Alicia" : "Roberto");

return (0);

}