Class 13: Game Theory I

02-24-2020

“You don’t have to be a mathematician to have a feel for numbers”

When we talk about game theory in competitive programming we mean combinational game theory. In combinatorial game theory we study combinatorial games, these are two-person games with perfect information and no change moves, and with a win-or-lose outcome. We can define such games using:

- Set of possible positions

- Initial position

- Set of terminal positions

- Player that starts the game

- Function that determines the possible moves from each position

If the function that determines the possible moves from each position is the same for both players, then we have a impartial game, else we have a partizan game. For each type (impartial and partizan) there are different strategies to solve them as we can see in the following diagram:

We will focus our study in these strategies and techniques.

A simple take-away game

Problem: There is a pile of \(n\) chips and two players (player A and player B). They are alternating turns, in each turn a player removes one, two or three chips from the pile. The player that removes the last chip wins. If player A starts the game and both players play optimally, who will be the winner ?

In order to solve this problem we can use what is called backward induction. This technique consists in analyzing a problem from the end back to the begining.

Let:

- \(L\): losing position for player A

- \(W\): winning position for player A

We can define a function \(f: \mathbb{N \cup \{0\}} \to \{L, W\}\) such that \(f(x)\) indicates what is the result for player A if the game has a pile of \(x\) chips.

From these definitions we have:

- \(f(0) = L\)

- \(f(1) = W\)

- \(f(2) = W\)

- \(f(3) = W\)

- \(f(4) = L\)

- \(f(5) = W\)

- \(f(6) = W\)

- \(f(7) = W\)

- \(f(8) = L\)

- \(f(9) = W\)

- \(f(10) = W\)

- \(f(11) = W\)

- \(f(12) = L\)

That is, if there are no chips, then player \(A\) loses. If there are \(1, 2\) or \(3\) chips, then player \(A\) can take all the chips in a move and win. If there are \(4\) chips no matter how many chips player \(A\) takes because player \(B\) can finish the game in the next turn. If there are \(5, 6\) or \(7\) chips, then player \(A\) can left just \(4\) chips, then no matter how many chips player \(B\) takes in its turn, in the next turn player \(A\) can take all the remaining chips, and so on.

From these we notice that \(f(n) = L \leftrightarrow n \equiv 0 \bmod 4\). Then, we have solved the problem.

The idea of defining a function that maps some states to \(L, W\) is what is called WL states. Moreover, we can generalize this idea with the following property:

Characteristic property

WL states are defined recursively by the following three statements:

- All terminal positions are \(L\) states.

- From every \(W\) state, there is at least one move to a \(L\) state.

- From every \(L\) state, every move is to a \(W\) state.

We can interpret these statements in this way:

- If I am in a terminal state, then I have no available moves, so I am in a losing state.

- If I can make that the other player starts its turn in a state where he will lose, then I am in a winning state.

- If I am in a state where no matter what I do, in the next turn the other player have a winning strategy, then I am in a losing state.

Now, let’s practice solving UVA 10404 - Bachet’s game.

It is basically a generalized version of ‘A simple take-away game’. The problem is the same, we still have a pile of \(n\) chips, but now the set of available moves (how many chips we can take) is variable.

We can use the characteristic property to solve the problem using backtracking in this way:

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int n, m;

vector <int> take;

const int L = 0;

const int W = 1;

int rec (int x) {

if (x == 0) { // terminal state

return L;

}

int result = L; // suppose we are in a losing state

for (int t: take) {

if (t <= x and rec(x - t) == L) {

// if there is a move to a losing state

// then we are in a winning state

result = W;

}

}

return result;

}

int main () {

int n, m;

while (cin >> n >> m) {

take.resize(m);

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) cin >> take[i];

if (rec(n) == W) cout << "Stan wins" << '\n';

else cout << "Ollie wins" << '\n';

}

return (0);

}The solution is correct, but it takes too much time doing the same computations. However, we can memorize some results and improve the solution in this way:

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int n, m;

vector <int> take;

vector <int> memo;

const int L = 0;

const int W = 1;

const int UNVISITED = 2;

int rec (int x) {

if (x == 0) { // terminal state

return L;

}

if (memo[x] != UNVISITED) { // we have already compute it

return memo[x];

}

int result = L; // suppose we are in a losing state

for (int t: take) {

if (t <= x and rec(x - t) == L) {

// if there is a move to a losing state

// then we are in a winning state

result = W;

}

}

return memo[x] = result;

}

int main () {

while (cin >> n >> m) {

take.resize(m);

memo.resize(n + 1, UNVISITED);

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) cin >> take[i];

if (rec(n) == W) cout << "Stan wins" << '\n';

else cout << "Ollie wins" << '\n';

take.clear();

memo.clear();

}

return (0);

}We are now solving each case in \(O(nm)\) which is enough to get the accepted veredict.

Problem: There are \(n\) piles of chips \(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\). There are two players (player A and player B) that are alternating turns. In each turn a player selects a pile (only one) and removes at least one chip from it. The winner is the player who removes the last chip. If player A starts the game and both players play optimally, who will be the winner ?

We can play this game in this link.

Now, in order to solve this problem first let’s define what is ‘Nim-sum’.

Def. Nim-sum: The Nim-sum of two non-negative integers is their addition without carry in base 2. In other words, let \(c\) be the Nim-sum of \(a\) and \(b\), filling zeros to the left as necessary so that \(a\) and \(b\) have the same number of digits. Then \(c_i = (a_i + b_i) \bmod 2\) and it is written as \(c = a \oplus b\).

\[a = \overline{a_na_{n-1} \dots a_1}_{(2)}\] \[b = \overline{b_nb_{n-1} \dots b_1}_{(2)}\] \[c = \overline{c_nc_{n-1} \dots c_1}_{(2)}\]

That is, \(a \oplus b\) is this in C++:

int c = a ^ b;The \(\oplus\) operator is called the xor operator and it has some interesting properly, for example:

- \(a \oplus b = b \oplus a\)

- \(a \oplus 0 = a\)

- \((a \oplus b) \oplus c = a \oplus (b \oplus c)\)

- \(a \oplus a = 0\)

This definition is important because we can use it to characterize the set of winning states using the characteristic property. In fact, it is done in the following theorem:

Bouton’s theorem

Let \(\mathbb{L}\) be the set of losing states and \(\mathbb{W}\) the set of winning states. Then, the solution of the game of Nim with piles \(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\) is characterized in this way:

\[(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) \in \mathbb{L} \leftrightarrow \displaystyle\bigoplus_{1 \leq i \leq n} x_i = 0\]

Proof:

- The only terminal position is \((0, 0, \dots, 0)\) and \(0 \oplus 0 \oplus \dots \oplus 0 = 0\).

- Let \((x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) \in \mathbb{W}\), then \(\displaystyle\bigoplus_{1 \leq i \leq n} x_i \not = 0\), so is we write all the numbers in binary representation in a matrix form, there exists a column \(k\) (let’s take the leftmost) such that the number of ones in this column is odd. So we can take a number of chips from a pile that have a \(1\) in this column. Moreover let \(p = \overline{p_{n}p_{n-1}\dots p_{k} \dots p_1}_{(2)}\) be the number of chips taken from this pile, then we can form \(p\) in such a way that \(p_i = 0, \forall i \geq k\) and \(\forall i < k, p_i\) can be \(0\) or \(1\), then we can form it in such a way that the Nim-sum of the new state would be 0. In other words, there is a losing state reachable from a winning state.

- Let \((x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) \in \mathbb{L}\). If we take the pile \(k\) and take some chips such that \(x_k\) reduces to \(x_k' < x_k\), then the new state have Nim-sum different from zero (You can prove it by contradiction).

We can use the above theorem to solve 10165 - Stone Game.

The statement is basically the game of Nim. Then, this is a possible solution:

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int main () {

int n;

while (cin >> n, n != 0) {

int nim_sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

int x;

cin >> x;

nim_sum ^= x;

}

puts(nim_sum == 0 ? "No" : "Yes");

}

return (0);

}We can express the characteristic property in a slighty different way. First, let’s define:

\[g(state) = \min(n \geq 0: n \not = g(state') \, \forall state \to state')\]

Where \(state \to state'\) means that we can go from \(state\) to \(state'\).

In other words, \(g(state)\) is the smallest non-negative integer not found amoung the function \(g\) evaluated in states reachable from \(state\).

The function \(g\) is known as the Spragre-Grundy function and its values as Grundy numbers or Nim values. What is nice about this function is that \(g(state) = 0 \leftrightarrow state \text{ is a losing state}\).

Moreover, there exists the function \(mex\) (a.k.a minimum excludant) that gives the smallest non-negative integer not found in a set. For example:

\[mex(\{0, 1, 3, 4, 5\}) = 2\] \[mex(\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5\}) = 0\] \[mex(\{3, 4, 5\}) = 0\] \[mex(\{0, 1\}) = 2\]

Then, we can define \(g\) in terms of the \(mex\) function in this way:

\[g(state) = mex(g(state') \, \forall state \to state')\]

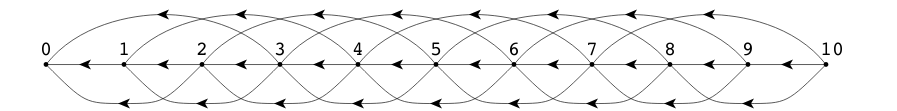

Now, all the problems that we can solve with the characteristic property can also be solved using its Grundy numbers. For example, for the first problem we solved (‘A simple take-away game’) the transitions can be seen in this way:

Image taken from Game theory - Thomas S. Ferguson. Page 14

Now, we can compute its Grundy numbers and we’ll get:

- \(mex(0) = 0\)

- \(mex(1) = 1\)

- \(mex(2) = 2\)

- \(mex(3) = 3\)

- \(mex(4) = 0\)

- \(mex(5) = 1\)

- \(mex(6) = 2\)

- \(mex(7) = 3\)

- \(mex(8) = 0\)

- \(mex(9) = 1\)

- \(mex(10) = 2\)

- \(mex(11) = 3\)

- \(mex(12) = 0\)

Then, we get the same result: \(n\) is a losing position \(\leftrightarrow n \equiv 0 \bmod 4\).

And we can even solve UVA 10404 - Bachet’s game but now using the \(mex\) function in this way:

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int n, m;

vector <int> take;

vector <int> memo;

const int UNVISITED = -1;

int grundy (int x) {

if (x == 0) { // terminal state

return 0; // mex 0

}

if (memo[x] != UNVISITED) { // we have already compute it

return memo[x];

}

set <int> values;

for (int t: take) {

if (t <= x) {

values.insert(grundy(x - t));

}

}

int mex = 0;

while (values.count(mex)) mex++;

return memo[x] = mex;

}

int main () {

while (cin >> n >> m) {

take.resize(m);

memo.resize(n + 1, UNVISITED);

for (int i = 0; i < m; i++) cin >> take[i];

if (grundy(n) != 0) cout << "Stan wins" << '\n';

else cout << "Ollie wins" << '\n';

take.clear();

memo.clear();

}

return (0);

}Now, we are solving each case in \(O(nm \log m)\) which is enough to get the accepted veredict. Could it be implemented in \(O(nm)\)?

But the importante of this new interpretation of the characteristic property can be better seen in the next section.

So faw we have seen how to solve impartial combinatorial games using WL states and Grundy numbers. Now, what happend if we form a game as the sum of several impartial combinatorial games ? Well, in this case the following theorem comes in handy:

The Sprague-Grundy theorem

Given \(n\) impartial combinatorial games, the Sprage-Grundy function of the union of these games is the Nim-sum of the Sprague-Grundy function of these games.

The proof is left to the reader as an exercise .

Now, let’s see some examples of this theorem:

First problem

Problem: The problem is the same of ‘A simple take-away game’, but now there are \(n\) piles of chips and in each turn a player can select a pile (only one) and removes one, two or three chips from this pile.

Let \(x_i\) be the number of chips in the \(i\)-th pile. Then, we can solve the problem using WL states or Grundy numbers. Now, our state will be \((x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n)\) and from this state we can go to these states (if possible):

- \((x_1 - 1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n)\)

- \((x_1 - 2, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n)\)

- \((x_1 - 3, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n)\)

- \((x_1, x_2 - 1, x_3, \dots, x_n)\)

- \((x_1, x_2 - 2, x_3, \dots, x_n)\)

- \((x_1, x_2 - 3, x_3, \dots, x_n)\)

- \((x_1, x_2, x_3 - 1, \dots, x_n)\)

- \((x_1, x_2, x_3 - 2, \dots, x_n)\)

\((x_1, x_2, x_3 - 3, \dots, x_n)\)

\(\vdots\)

- \((x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n - 1)\)

- \((x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n - 2)\)

\((x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n - 3)\)

That is, from every state there are \(O(3n) = O(n)\) possible transitions. So, we can calculate the Grundy number of the state \((x_1, x_2, x_3, \dots, x_n)\) in \(O(n \cdot x_1 \cdot x_2 \cdot \dots \cdot x_n) = O(n x^n)\) where \(x = \max(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)\).

But, if we use the Sprague-Grundy theorem, we can compute the Grundy number of the state \((x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)\) in this way:

\[g(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n) = g(x_1) \oplus g(x_2) \oplus \dots \oplus g(x_n)\]

And we can compute all \(g(x_1), g(x_2), \dots, g(x_n)\) at the same time using memorization (the first solution we give to UVA 10404 - Bachet’s game) in \(O(3x) = O(x)\). Then, we can compute \(g(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n)\) in \(O(x + n)\). Can you implement it?

Second problem

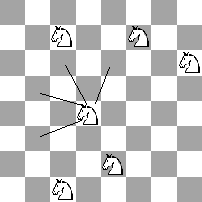

Problem: Given a \(N \times N\) chessboard with \(K\) knights on it. Each knight can move only as shown in the picture below. There can be more than one knight on the same square at the same time. Two players take turns moving and in each turn a player chooses one of the knights and moves it. The player who is not able to make a move is declared the loser. If both players play optimally who will win ?

Image and problem taken from Algorithm Games - Topcoder

In order to solve this problem we can see each knight as a different game, then we have the union of games, so the Grundy number of our game is the Nim-sum of the Grundy number of the positions of the knights.

In code it may be something like this:

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

int n;

vector <string> board;

vector <vector <int>> memo;

const int UNVISITED = -1;

const vector <int> dr = {1, -1, -2, -2};

const vector <int> dc = {-2, -2, -1, 1};

int grundy (int r, int c) {

if (memo[r][c] != UNVISITED) {

return memo[r][c];

}

set <int> values;

for (int d = 0; d < dr.size(); d++) {

int nr = r + dr[d];

int nc = c + dc[d];

if (0 <= min(nr, nc) and max(nr, nc) < n) {

values.insert(grundy(nr, nc));

}

}

int mex = 0;

while (values.count(mex)) mex++;

return memo[r][c] = mex;

}

int main () {

/* Input example

8

........

..K..K..

.......K

........

...K....

........

....K...

..K.....

*/

cin >> n;

board.resize(n);

memo = vector <vector <int>> (n, vector <int> (n, UNVISITED));

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) cin >> board[i];

vector <int> values;

for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) {

for (int c = 0; c < n; c++) {

if (board[r][c] == 'K') {

values.push_back(grundy(r, c));

}

}

}

int mex = 0;

for (int elem: values) {

mex ^= elem;

}

if (mex == 0) {

cout << "The first player is in a losing state" << '\n';

} else {

cout << "The first player is in a winning state" << '\n';

}

return (0);

}We may have also solved the problem using WL states or just Grundy numbers, but then we would have needed to analyze around \(\binom{N \cdot N}{K}\) possibles states, whereas using the Sprague-Grundy theorem we solved the problem in \(O(N ^ 2)\).

Recommended readings:

- Game theory - Thomas S. Ferguson. Chapter 1-4

- Ali Ibrahim Site - Game Theory

- Algorithm Games - Topcoder

- Game Theory For Competitive Programming

You can find the contest here.

A: The Game

The Game

Having \(x\) stones in square \(i\) is equivalent to having \(x\) piles of size \(i\), then we can reduce the problem to the game of Nim.

Extra: What happend if you have an even number of equal size piles ?

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#define all(A) begin(A), end(A)

#define rall(A) rbegin(A), rend(A)

#define sz(A) int(A.size())

#define pb push_back

#define mp make_pair

using namespace std;

typedef long long ll;

typedef pair <int, int> pii;

typedef pair <ll, ll> pll;

typedef vector <int> vi;

typedef vector <ll> vll;

typedef vector <pii> vpii;

typedef vector <pll> vpll;

int main () {

ios::sync_with_stdio(false); cin.tie(0);

int tc;

cin >> tc;

while (tc--) {

int n;

cin >> n;

int nim_sum = 0;

for (int i = 1; i <= n; i++) {

int x;

cin >> x;

while (x--) nim_sum ^= i;

}

if (nim_sum == 0) cout << "Hanks Wins\n";

else cout << "Tom Wins\n";

}

return (0);

}B: Stone Game

Stone Game

If there are \(x\) stones in the \(i\) pile, then you will play \(\lfloor \frac{x}{i} \rfloor\) turns with this pile. Then, you may realize that the total number of turns is fixed, so we just need to checks its parity.

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#define all(A) begin(A), end(A)

#define rall(A) rbegin(A), rend(A)

#define sz(A) int(A.size())

#define pb push_back

#define mp make_pair

using namespace std;

typedef long long ll;

typedef pair <int, int> pii;

typedef pair <ll, ll> pll;

typedef vector <int> vi;

typedef vector <ll> vll;

typedef vector <pii> vpii;

typedef vector <pll> vpll;

int main () {

ios::sync_with_stdio(false); cin.tie(0);

int tc;

cin >> tc;

while (tc--) {

int n;

cin >> n;

int n_turns = 0;

for (int i = 1; i <= n; i++) {

int x;

cin >> x;

n_turns ^= (x / i);

}

if (n_turns % 2 == 0) cout << "BOB\n";

else cout << "ALICE\n";

}

return (0);

}C: Exclusively Edible

Exclusively Edible

The problem reduces to the game of Nim with four piles (the number of cell that there are above, below, to the left and to the right of the given position).

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#define all(A) begin(A), end(A)

#define rall(A) rbegin(A), rend(A)

#define sz(A) int(A.size())

#define pb push_back

#define mp make_pair

using namespace std;

typedef long long ll;

typedef pair <int, int> pii;

typedef pair <ll, ll> pll;

typedef vector <int> vi;

typedef vector <ll> vll;

typedef vector <pii> vpii;

typedef vector <pll> vpll;

int main () {

ios::sync_with_stdio(false); cin.tie(0);

int tc;

cin >> tc;

while (tc--) {

int m, n, r, c;

cin >> m >> n >> r >> c;

int pile1 = r;

int pile2 = m - r - 1;

int pile3 = c;

int pile4 = n - c - 1;

if ((pile1 ^ pile2 ^ pile3 ^ pile4) == 0) cout << "Hansel\n";

else cout << "Gretel\n";

}

return (0);

}D: Exponential Game

Exponential Game

The number of possible transitions is low, then we basically have the union of take away games, so we can compute the Grundy number of each pile and use the Sprage-Grundy theorem to solve the whole problem.

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

vector <int> take;

vector <int> memo;

const int UNVISITED = -1;

int grundy (int x) {

if (x == 0) { // terminal state

return 0; // mex 0

}

if (memo[x] != UNVISITED) { // we have already compute it

return memo[x];

}

set <int> values;

for (int t: take) {

if (t <= x) {

values.insert(grundy(x - t));

}

}

int mex = 0;

while (values.count(mex)) mex++;

return memo[x] = mex;

}

int main () {

const int N = 1e5 + 1;

int cur = 1;

while (true) {

int power = 1;

for (int i = 0; i < cur; i++) {

power *= cur;

}

if (power >= N) break;

take.push_back(power);

cur++;

}

memo.resize(N, UNVISITED);

int tc;

cin >> tc;

while (tc--) {

int n;

cin >> n;

int nim_sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

int x;

cin >> x;

nim_sum ^= grundy(x);

}

if (nim_sum == 0) cout << "Head Chef\n";

else cout << "Little Chef\n";

}

return (0);

}E: Bob’s Game

Bob’s Game

Each king can be seen as a different game, then we can just compute its Grundy number and use the Sprage-Grundy theorem. Moreover, we can compute the number of winning moves using the Sprage-Grundy theorem when we make a move (xor properties comes in handy here).

Code

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

#define all(A) begin(A), end(A)

#define rall(A) rbegin(A), rend(A)

#define sz(A) int(A.size())

#define pb push_back

#define mp make_pair

using namespace std;

typedef long long ll;

typedef pair <int, int> pii;

typedef pair <ll, ll> pll;

typedef vector <int> vi;

typedef vector <ll> vll;

typedef vector <pii> vpii;

typedef vector <pll> vpll;

int main () {

ios::sync_with_stdio(false); cin.tie(0);

const int UNVISITED = -1;

int q;

cin >> q;

while (q--) {

int n;

cin >> n;

vector <string> grid(n);

for (auto& s: grid) cin >> s;

vector <vi> memo(n, vi(n, UNVISITED));

auto get_moves = [&] (int r, int c) {

vpii moves;

if (0 <= r - 1 and grid[r - 1][c] != 'X') {

moves.pb(pii(r - 1, c));

}

if (0 <= c - 1 and grid[r][c - 1] != 'X') {

moves.pb(pii(r, c - 1));

}

if (0 <= min(c - 1, r - 1) and grid[r - 1][c - 1] != 'X') {

moves.pb(pii(r - 1, c - 1));

}

return moves;

};

function <int(int,int)> grundy = [&] (int r, int c) -> int {

if (memo[r][c] != UNVISITED) return memo[r][c];

vpii nxt = get_moves(r, c);

set <int> values;

for (auto pp: nxt) {

values.insert(grundy(pp.first, pp.second));

}

int mex = 0;

while (values.count(mex)) mex++;

return memo[r][c] = mex;

};

int nim_sum = 0;

for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) {

for (int c = 0; c < n; c++) {

if (grid[r][c] != 'K') continue;

nim_sum ^= grundy(r, c);

}

}

if (nim_sum == 0) {

cout << "LOSE\n";

continue;

}

int ways = 0;

for (int r = 0; r < n; r++) {

for (int c = 0; c < n; c++) {

if (grid[r][c] != 'K') continue;

vpii nxt = get_moves(r, c);

for (auto pp: nxt) {

if ((nim_sum ^ grundy(r, c) ^ grundy(pp.first, pp.second)) == 0) {

ways++;

}

}

}

}

cout << "WIN " << ways << '\n';

}

return (0);

}